4641Project

Predicting Chess Match Results Based on Opening Moves

Team Members: Samia Khan, Minseo Kwak, Ethan Jones, and Kyle Keirstead

Introduction

Chess has been studied as a subject of artificial intelligence for many decades, which is why it has been described as, “the most widely-studied domain in the history of artificial intelligence” (Silver et al. 1). Ranging back all the way to the 1950s, various aspects of the game have been studied; one of the most notable instances of this is IBM’s Deep Blue computer. In 1997, Deep Blue beat chess champion Garry Kasparov (“Deep Blue”), proving AI’s ability to compete against (and beat) the best human chess players.

Given that IBM was able to achieve this over 20 years ago and technology has only continued to evolve, our team chose to focus on creating something that has the ability to derive conclusions from prior player performance and the opening moves used in a chess match. Chess always begins with the same initial board layout; as a result, different combinations of opening moves occur frequently in play and have the potential to be used to predict the outcome of the match at a very early stage. Point systems in chess are often used as the game progresses as a measure of which player holds an advantage; however, our work studies the earliest moves in the game (before players generally begin trading pieces).

Our goal is to predict the likelihood that the result of a chess game can be predicted using only the knowledge of the first x moves and the ratings of the two players involved in the match. Initially, we believed that this may be beneficial for helping players to choose certain openings; though our work may be useful in this respect, the choice of moves should be viewed as a causality of the player’s experience. As a result, an inexperienced player making the moves in a bid to play better may yield moderate performance gains, but ultimately the opening moves lead to victory not because they are superior, but because the player making them is superior and recognizes the advantages of using certain openings.

Results and Discussion

The Data

Source: https://www.kaggle.com/datasnaek/chess

Our team utilized a data-source that provided information on over 20,000 games played on the website Lichess.org. The set included data on both sets of players, the game’s duration, the end result, all moves (in Standard Chess Notation), the names of the openings used by both players, and other miscellaneous information.

For our project, the team only used a subset of the available features. These include the rating of each player, the first 10 moves for each player, and the result of the game. Though the data provided information on the name of the specific openings used by each player, these openings are associated with a specific number of moves at the beginning of the match. We elected to manually evaluate the openings by using the raw move data for an increasing number of moves to prevent the possibility of overlooking the importance of different numbers of moves.

Approach

Our team utilized Supervised Machine Learning for our project. When drafting our initial proposal, we discussed a variety of different techniques and how well they would align with our goal. We realized that the hierarchy of potential chess moves from a single starting state resembled a tree with branches that extend to represent different combinations of moves. As a result, we chose to utilize decision trees.

In creating decision trees, each combination of moves represents a node. Using a Python dictionary, these move combinations serve as a key, and the games that correspond to each opening sequence of moves are stored as a list of values. To limit overfitting, we split our game data as follows: 80% training data and 20% testing data. For each key in the training data, we used the players’ ratings and the result of the game (white wins, black wins, or stalemate) to train the decision tree. After completing the training, we ran the decision tree on the testing data and compared the predicted result of the game to the actual outcome.

This procedure was performed 10 times; initially, only the first move for each player was being considered, and in each iteration another move was added, and a new list of keys was formed until the keys represented the first 10 moves of the game. As more moves were added, the tree began to branch out, and an increasing number of potential sequences of moves appeared as keys. As a result, one-off instances began to occur; with only one piece of data corresponding to a certain key, it was impossible to split into training and testing data, and in these situations the key was not included in our findings.

To visualize our results, we generated plots.

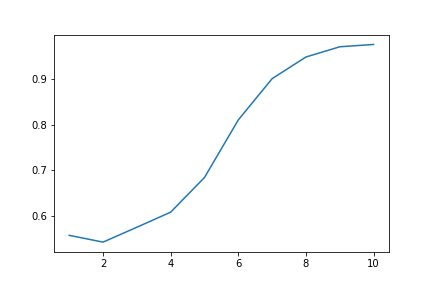

Accuracy graph as opening length increases:

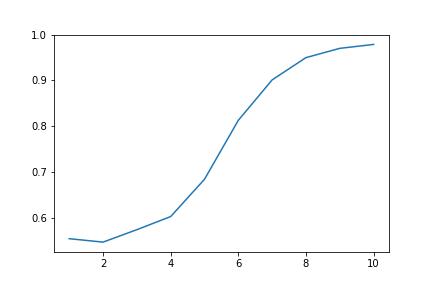

Precision graph as opening length increases:

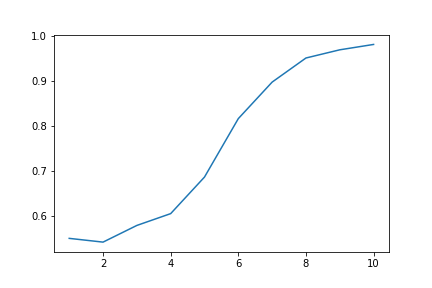

Recall graph as opening length increases:

Conclusion

What We Accomplished

Initially, our ideal outcome was an algorithm that predicted the result of the whole game based on the ratings and initial moves of both players with a high degree of accuracy. After receiving feedback on our proposal, we also decided to take precision and recall into account. From our plots, it is apparent that using only one move for the opening is insufficient because the accuracy is only about 55%. By increasing the number of moves in the opening, accuracy increases to over 95% (when considering the opening 10 moves), which we consider to be a high success rate for the scope of our project. Additionally, our models were tested for precision and recall (as shown in the plots above); these behaved very similarly to accuracy.

Future Work

In the future, our primary focus would revolve around using a larger dataset that offered more diversity in where its data was sampled. The dataset used in this project had 20,000 games, and though this is a significant amount of games, the increased branching as more opening moves were considered limited our ability to draw conclusions when considering higher amounts of opening moves.

We would also be interested in seeing how our results would change after including more features in the decision tree’s training. For example, would the average amount of time a player spends making each move help indicate their confidence and skill? The team was also interested in exploring the opening moves’ significance as a fraction of the total number of moves in the game. This would mean that the first three moves in a game of thirty moves would be treated equivalently to evaluating the first eight moves in a game of eighty moves.

References

Chassy, Philippe, and Fernand Gobet. “Measuring Chess Experts’ Single-Use Sequence Knowledge: an Archival Study of Departure from ‘Theoretical’ Openings.” PloS One, Public Library of Science, 16 Nov. 2011 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3217924/.

“Deep Blue.” IBM100 - Deep Blue, IBM www.ibm.com/ibm/history/ibm100/us/en/icons/deepblue/.

Silver, David, et al. “Mastering Chess and Shogi by Self-Play with a General Reinforcement Learning Algorithm.” ArXiv.org, Cornell University, 5 Dec. 2017 arxiv.org/abs/1712.01815v1.